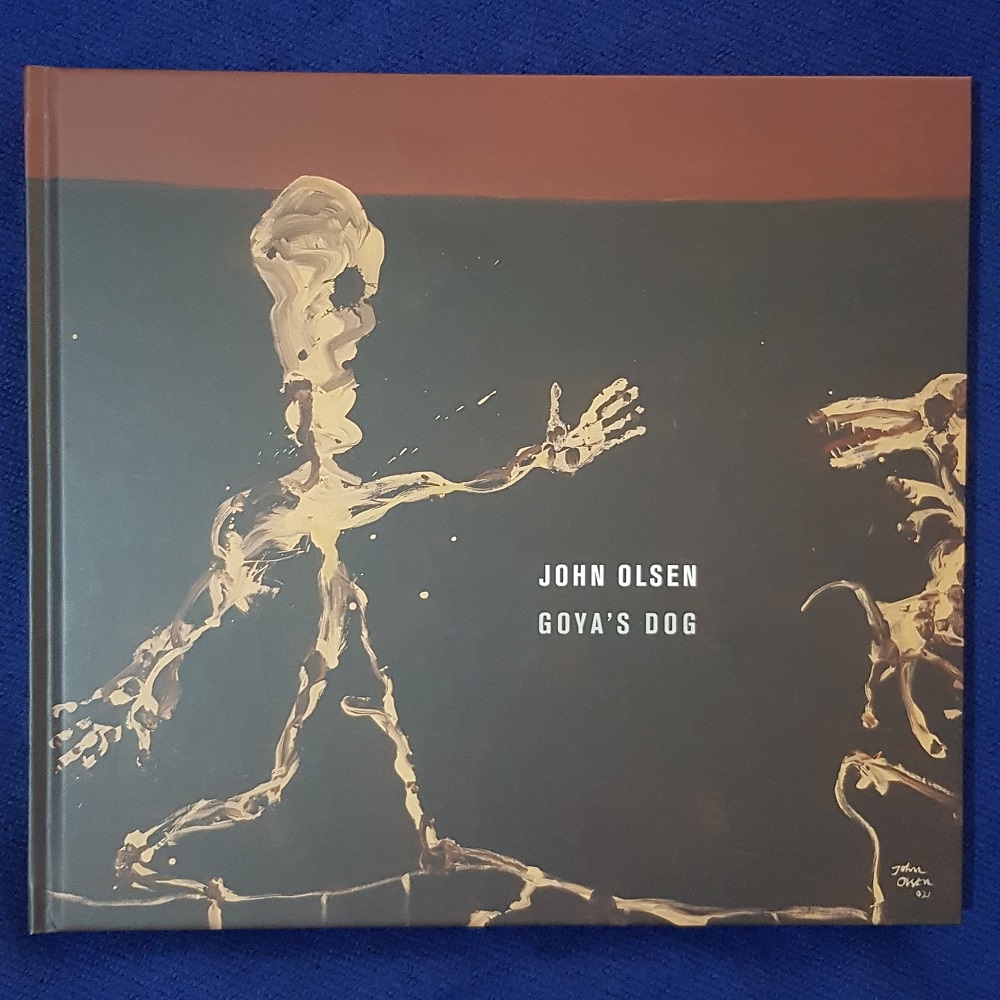

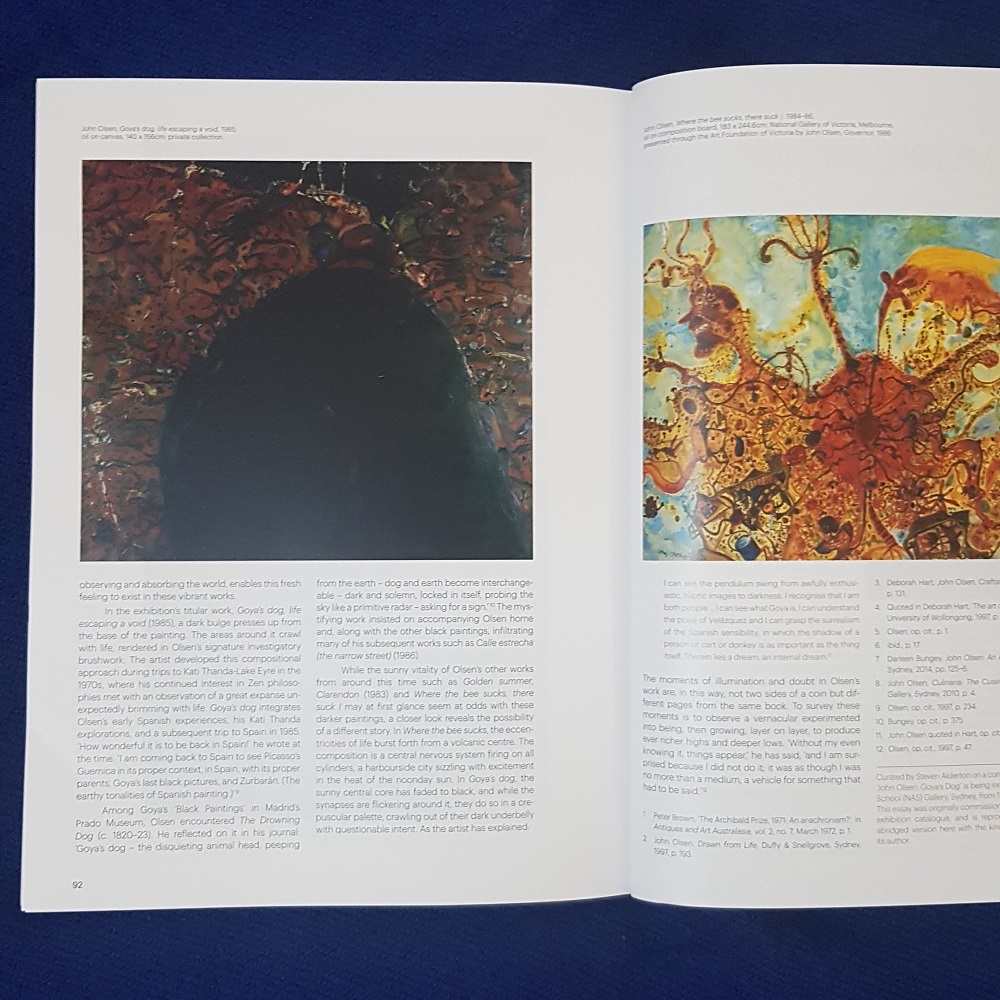

John Olsen: Goya’s Dog (at the National Art School, Sydney from 11 June to 7 August 2021) spans eight decades of the artist’s practice, from the 1950s, when he first visited Spain, to the present. This exhibition tracks the influences of these Spanish encounters on the artist’s sensibility, his palette, and how he views the landscape and the human condition. It delves into the introspection and darker elements that pervade his work, and contrasts these with the sunny, more exuberant aspects of his practice. Goya’s Dog features over 50 major works, sketchbooks and drawings, many not seen in public for generations.

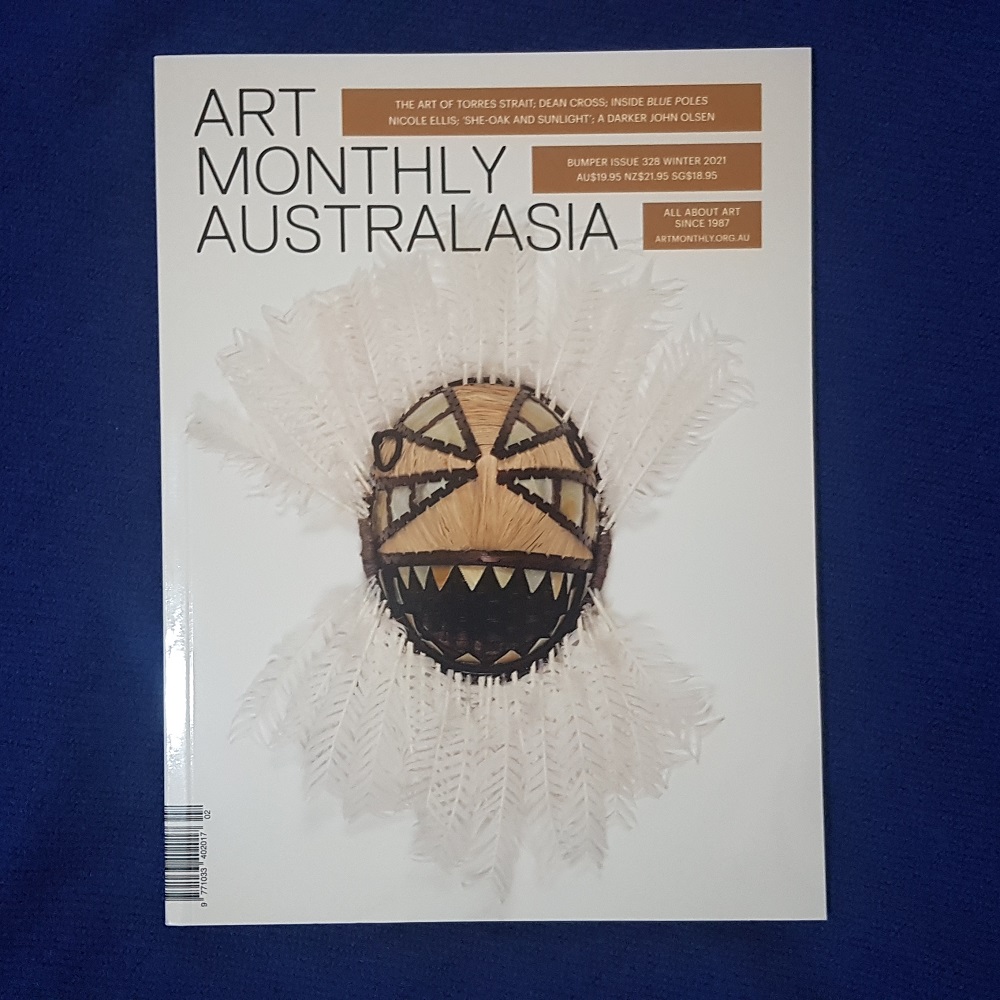

I was honoured to be invited to write the catalogue essay for the publication that accompanies John Olsen: Goya’s Dog. Excerpts from this essay appear on the wall labels throughout the exhibition, and an abridged version also appears in Art Monthly Australasia issue 328 (Winter 2021). Read the introduction below:

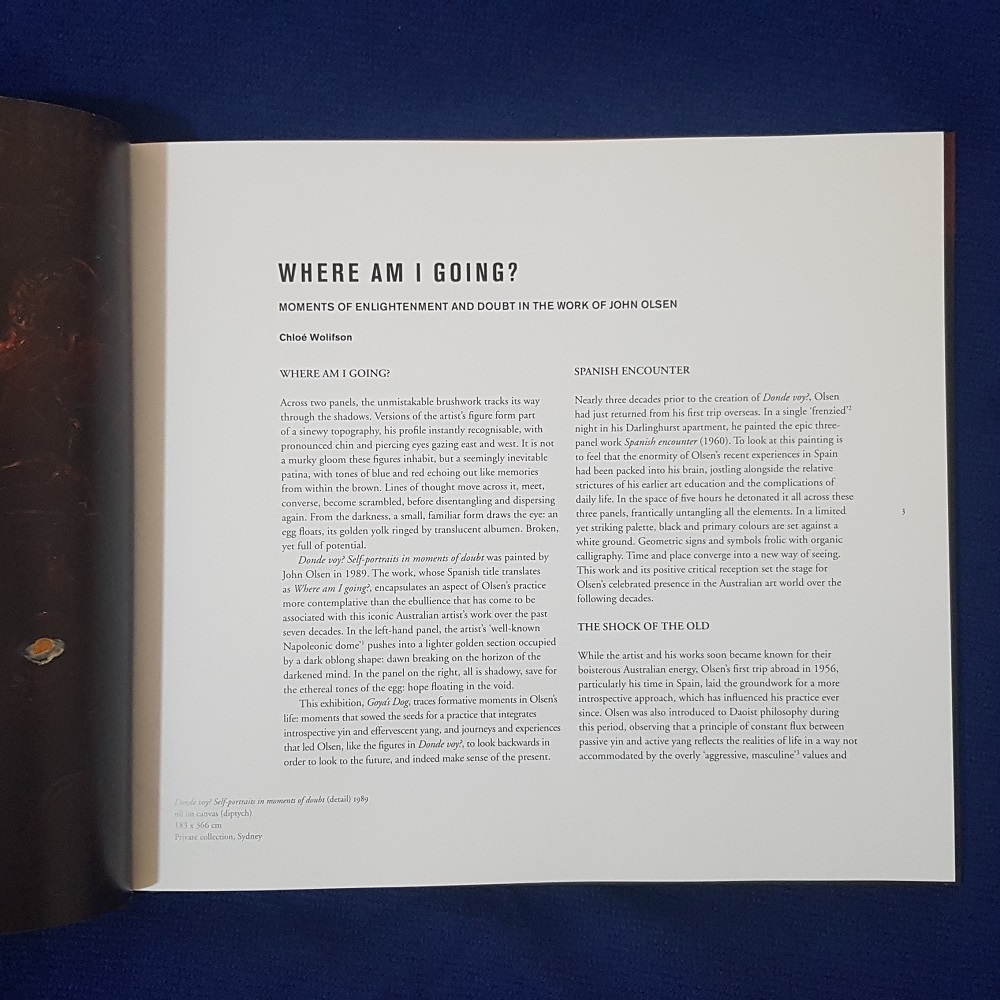

“Across two panels, the unmistakeable brushwork tracks its way through the shadows. Versions of the artist’s figure form part of a sinewy topography, his profile instantly recognisable, with pronounced chin and piercing eyes gazing east and west. It is not a murky gloom these figures inhabit, but a seemingly inevitable patina, with tones of blue and red echoing out like memories from within the brown. Lines of thought move across it, meet, converse, become scrambled, before disentangling and dispersing again. From the darkness, a small, familiar form draws the eye: an egg floats, its golden yolk ringed by translucent albumen. Broken, yet full of potential.

Donde voy? Self-portraits in moments of doubt was painted by John Olsen in 1989. The work, whose Spanish title translates as Where am I going?, encapsulates an aspect of Olsen’s practice more contemplative than the ebullience that has come to be associated with this iconic Australian artist’s work over the past seven decades. In the left-hand panel, the artist’s ‘well-known Napoleonic dome’[i] pushes into a lighter golden section occupied by a dark oblong shape: dawn breaking on the horizon of the darkened mind. In the panel on the right, all is shadowy, save for the ethereal tones of the egg: hope floating in the void.

The National Art School Gallery exhibition ‘Goya’s Dog’ traces formative moments in Olsen’s life: moments that sowed the seeds for a practice that integrates introspective yin and effervescent yang, and journeys and experiences that led Olsen, like the figures in Donde voy?, to look backwards in order to look to the future, and indeed make sense of the present.”

[i] P. Brown, ‘The Archibald Prize, 1971: An anachronism?’, in Antiques and Art Australasia, vol. 2, no. 7, March 1972, p. 1.