In late February I spent ten days in Hong Kong with a group of friends. With the happy excuse of a friend’s wedding to attend, I of course couldn’t let the trip pass without a visit to some of the city’s contemporary galleries.

Having briefly experienced the more established Hollywood Road precinct on a previous trip, I decided this time to focus on the flashier side of things. With six friends accompanying me around the busy streets, it seemed wise to keep things geographically focussed. Armed with some tips from Texan-Australian artist Eric Niebhur, who has made his temporary home in the city, I decided on two complexes in Central – the Pedder Building and 50 Connaught Road.

The jewel in the Pedder Building crown is the Hong Kong branch of Gagosian Gallery, which, as luck would have it, was in between shows the day we visited. Not ones to be put off so early in our endeavours, we descended a level (in one of the city’s more agreeable lifts) to Pearl Lam Galleries, where the renowned restaurateur Mr Chow, aka Zhou Yinghua, was holding his first solo exhibition in five decades, Recipe for a painter.

Michael Chow aka Zhou Yinghua, Rite of Spring 1, 2013, Mixed media: household paint with precious metals & trash, 243.8 x 183 cm, Courtesy the artist and Pearl Lam Galleries, Photography: Fredrik Nilsen

Zhou’s large-scale canvases are laden with detritus. Delicately resting eggshells, and rubber gloves emerging zombie-like from the works’ surfaces, refer obliquely to a painter’s studio practice. However these chaotic details belie the overall seductive effect of Zhou’s work. While the rough scramblings of paint and objects breaking through the paintings’ grey, white and silver skins owe a debt to American abstract expressionism, these are thoughtfully interspersed with negative space in a manner bringing to mind traditional Chinese ink compositions. Abstracted landscape elements emerge and are submerged again, taking the viewer with them as we are drawn into examining what objects lies within these clusters.

Next stop on the gallery express was Hanart TZ Gallery. Like their neighbours Pearl Lam, Hanart was established over 20 years ago and is one of the few galleries in the building with a focus on Chinese art. However Yuan Jai’s Year of Abundance could not have been more different from Zhou’s work. These delicately painted polychromatic ink on silk works feature dreamscapes which make reference to diverse art historical traditions, from Indian miniatures to Surrealists. Simultaneously joyful and chaotic, there is a lot to see in Yuan’s works. In some paintings, religious totems and other cultural iconography commune with wildlife in sublime colour fields, while elsewhere, still life compositions have a psychoanalytic flavour. On another scale or with a more saturated palette, Yuan’s compositions might have seemed flamboyant; however the artist’s delicate treatment of her subject matter results in intriguing arrangements that invite contemplation.

Down the end of the hall from Hanart are the Hong Kong headquarters of art world heavy hitters Lehmann Maupin. Small but perfectly formed, the space (like the gallery’s other branches) was renovated by Pritzker Architecture Prize winner Rem Koolhaas. At the time of our visit it was inhabited by the immersive video installations of Jennifer Steinkamp. The LA-based artist’s exhibition Diaspore comprised two works, both projected at full wall-size in darkened rooms. In the exhibition’s namesake work, animated tendrils and leaves swirl around and bounce off the sides of the wall like particles in a jar of liquid. In Bouquet, a clump of organic matter gradually disperses through space. The effect of both works is immersive and hypnotic, taking the viewer on a journey through animation’s virtual space.

Jennifer Steinkamp, Diaspore I, 2014 (installation view), video installation, dimensions variable, edition of 3. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin. Photography: Kitmin.com

We were in for a change of pace on the third floor at the Europe-focussed gallery Ben Brown Fine Arts, with the self-titled exhibition by legendary French collaborators Claude & François-Xavier Lalanne (whose fans included Serge Gainsbourg who named an album after a Lalanne work). Animal, vegetable and mineral meet in these whimsical objects which are part functional sculpture, part decorative arts. Flora and fauna adorn and sometimes form furniture rendered in gold. Hybrids are the norm for Les Lalannes, such as an oxidised copper cabbage standing on chicken’s legs. One smaller room was occupied by the unlikely scene of a flock of oblong sheep-benches grazing on AstroTurf. Eccentricity at its best, and “equally suitable for traditional and contemporary environments” (according to the gallery website).

Claude & François-Xavier Lalanne, 2014, installation view, courtesy the artists & Ben Brown Fine Arts

Back to reality, we wandered down the hall to the more typically austere gallery setting of Simon Lee. Here the group exhibition Walk the line was showcasing the work of eight artists from the gallery’s predominantly European and American stable (this being an offshoot of the gallery’s main London branch). I was particularly excited to see the inclusion of Heimo Zobernig (whose exhibition in Madrid’s Palacio Velazquez blew away my husband and I when on our honeymoon last year) as well as Christopher Wool (who was recently given a survey show at New York’s Guggenheim). These artists’ abstract paintings, along with the others in Walk the line, are formed via a process more conceptual than intuitive, often involving the translation of an image numerous times resulting in changes or mutations. While aesthetically divergent, the works in the show share an investigation into the possibilities of the medium.

This completed our visit to the Pedder Building, so we resisted the urge to visit the chandelier-laden Abercrombie & Fitch trance palace next door, instead heading to Connaught Road as planned. The main event here is White Cube, a two-decade old establishment which currently spans two London spaces as well as one in São Paolo. In a city where life is lived at very close quarters, the Hong Kong spaces of White Cube are luxuriously expansive, with two floors both graced with high ceilings. Our group all immediately noticed the soft beige carpet underfoot, perhaps in place to absorb the noise from the busy road outside. If this is the intention it works, cocooning the visitor within a serene, well, white cube.

Sergej Jensen, Evian, 2014, installation view. Courtesy the artist and White Cube

Danish artist Sergej Jensen’s Evian is a collection of minimalist and slightly grungy paintings, in which the artist has used the existing condition of his materials as readymade marks. The subdued palette and subtle gestures of Jensen’s acrylic on linen works are quietly angst-ridden. One untitled piece made of wool was spread in the centre of the floor as if it had lain down in emotional exhaustion. Perhaps we could relate after cramming so many galleries into one afternoon; however there was one more stop on our itinerary. So up we went in another lift (this one was clad in white marble and gold and left the one in the Pedder Building for dead) to Galerie Perrotin.

Chen Fei, Jupiter 2013, acrylic on canvas, 170 x 130 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Perrotin

Perrotin has been around for 25 years and currently has sites in New York and Paris, so as expected its rooms in 50 Connaught Road were impressive to say the least. The main gallery space was playing host to a solo show by Japanese artist Izumi Kato, whose figurative paintings and sculptures display innovative application of paint and psychoanalytic undercurrents. In two smaller gallery spaces we found Chen Fei’s Flesh and Me. These paintings draw in the viewer with their incredible flatness and detail, only to confront with their subjects, mostly figures in nocturnal settings who display marks of intentional violence with quiet passivity.

The accidental star of the show at Galerie Perrotin, however, is the view of the harbour afforded from its place on the 17th floor. The gallery knows it, and has benches in place in front of the floor-to-ceiling windows allowing visitors to drink it in. On the one hand one feels for the artists whose work has to compete with the vista, but on the other it clears the mind and invites the audience to dwell longer in the space. This we did, enjoying some welcome respite from the frenetic pace of the city, before heading back out into it again for more Hong Kong adventures.

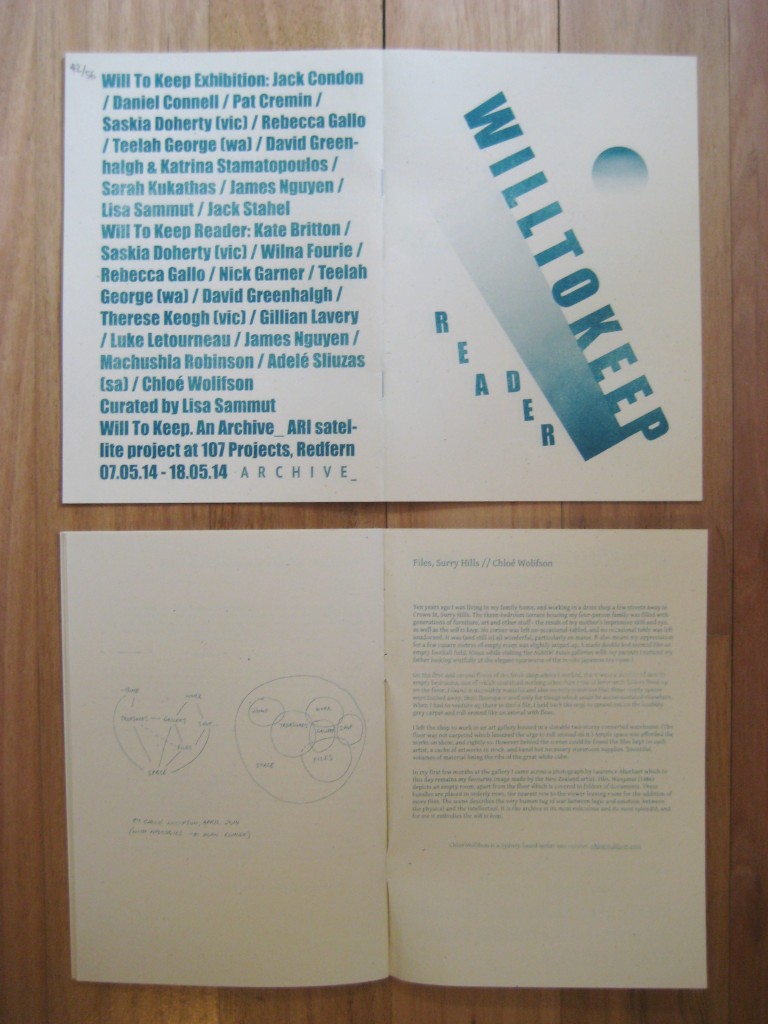

View from Galerie Perrotin on a typically smoggy Hong Kong day. Photograph by the author.